International Cooperation

International cooperation is essential for the successful recovery of assets that have been hidden abroad and its importance has been recognized through a number of treaties including UNCAC.

UNODC Mutual Legal Assistance Request Writer Tool

About International Cooperation

Corruption cases and most complex money laundering cases generally require asset recovery efforts beyond domestic borders. Some offences or parts of an offense may be committed in another jurisdiction: a company paying bribes for a contract may be headquartered or incorporated in a jurisdiction outside the jurisdiction in which the bribes are paid, and the officials receiving the bribes may launder their ill-gotten gains in still another jurisdiction. In addition, the international financial sector is a particularly attractive setting for those seeking to launder funds and impede asset tracing efforts. Intermediaries such as accountants, lawyers, or trust and company service providers, offer access to the financial sector and serve to disguise a corrupt official’s involvement in a transaction or ownership of assets. Those so called “gatekeepers” may offer yet another point of attack to go after the funds and thus potentially expand the number of jurisdictions involved.

Corrupt officials use complicated financial schemes often involving offshore centers, shell companies, and corporate vehicles to launder the proceeds of corruption- very easy and quick to set up. In addition, money can be moved quickly — often instantly with the click of a keyboard key or a cell phone button, with the help of such tools as wire transfers, letters of credit, credit and debit cards, automated teller machines, cryptocurrencies and mobile devices.

International cooperation is fundamental for the process of international asset recovery, as these cases often involve several jurisdictions through which monies are moved and assets are held. Successful asset recovery often depends on assistance from foreign jurisdictions. However, differences in legal traditions, law and procedures and even language often make the process of obtaining legal assistance cumbersome and difficult and recovery by law enforcement officials and prosecutors may take months or years because the principle of sovereignty restricts authorities’ ability to take investigative, legal, and enforcement actions in foreign jurisdictions.

The importance of this mechanism is further underscored by the fact that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has established that an effective international cooperation framework is essential for combatting money laundering and terrorism financing. Indeed, immediate outcome expects countries to deliver appropriate information, financial intelligence, and evidence, and facilitates action against criminals and their assets, including to identify, freeze, seize, confiscate and share assets.

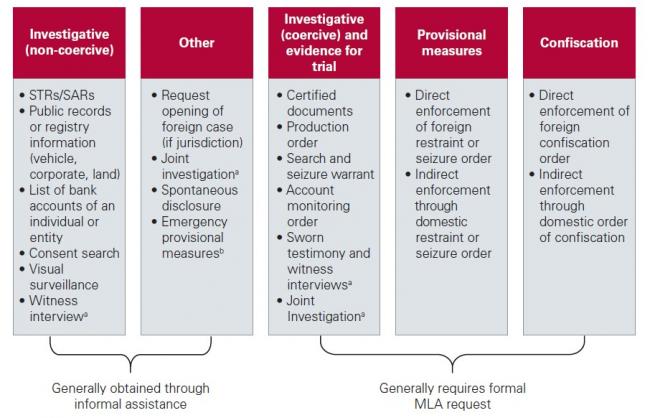

Differences between Informal and Formal International Cooperation

International cooperation is usually classified into informal assistance and formal assistance, depending on the purpose of the request and the requirements of the information. A combination of both is needed at various times of an investigation, and understanding their purpose, requirements and limitations is essential for successfully obtaining international cooperation.

|

Differences between Informal Assistance and MLA Requests |

||

|

Factor |

Informal assistance |

MLA requests |

|

Purpose |

|

|

|

Type of assistance |

Access to open information; Non-coercive investigative measures; proactive disclosure of closed information according to legal frameworks; joint investigation; opening of foreign case. |

Coercive investigative measures (such as search orders) and other forms of judicial assistance (such as enforcement of provisional measures or confiscation judgment). |

|

Contact process |

Direct: law enforcement, prosecutor, or investigating magistrate directly to counterpart, among Financial Intelligence Units, between banking & securities regulators. |

Generally, not direct: central authorities in each jurisdiction to proper contact point (law enforcement, magistrate, prosecutor, judge); a letters rogatory through the ministry of foreign affairs. |

|

Requirements |

|

May include dual criminality, reciprocity, specialty, ongoing criminal investigation, or link between assets and offense. |

|

Advantages |

|

Evidence is admissible in court; enables enforcement of orders. |

|

Limitations |

Information cannot always be disclosed without restrictions and/or used as evidence; difficult to determine contacts; few resources allocated to networking; potential leaks. |

Time-consuming; resource intensive; many requirements that are often difficult to meet; potential leaks. |

|

a. There may be bilateral or multilateral agreements that permit direct contact among practitioners. |

||

Informal Assistance

Informal assistance can be obtained quickly and is not subject to formalities. It is the process through which analysts, law enforcement or prosecutors informally contact counterparts or partner agencies to quickly obtain information that can support an investigation. Informal assistance can include (but is not limited to) obtaining information from property or company registries, drive-byes, verification of information in police databases or the identity of witnesses. Informal assistance can be extremely useful to determine the direction of an investigation and the need and scope of formal assistance. However, the information obtained is not considered evidence and cannot be introduced in a judicial process.

Informal legal assistance is built on trust and reliable networks and requires time and effort from all parties involved. Recognizing this, international organizations encourage building relationships among peers through international events, and promote the establishment of asset recovery networks, such as CARIN, RRAG, ARINSA, ARIN-AP, or ARIN-WCA. These networks bring together practitioners from multiple regions, who meet on a regular basis, and exchange information for the purpose of asset recovery.

Formal Assistance

Formal assistance on the other hand can be lengthy and is subject to procedure, but any information collected can be considered evidence that can be introduced into a judicial process. Formal assistance is also required when coercive measures are necessary, such as to impose preventive measures (i.e. freezing and seizing orders) or to obtain sensitive information (i.e. financial or tax information). Formal legal assistance can take many forms; the more traditional being letters rogatory, and the more modern being mutual legal assistance (MLA) requests.

Letters rogatory were the original formal requests for assistance, dating to the 1905 Civil Procedure Convention, signed at The Hague. Letters rogatory are based on reciprocity, in absence of a treaty. Because in the absence of a treaty courts are not able to communicate with each other directly, requests for assistance must go through a diplomatic channel. This usually means that the courts must issue the request, which is sent to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which in turn sends the request to the requested country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to be communicated to the domestic courts. This makes the process extremely lengthy and formal, taking away precious time from an investigation, which allows criminals to quickly move assets, destroy evidence or abscond.

The excessive lengthiness and formality of letters rogatory led to the introduction of mutual legal assistance requests (MLAs) via treaties. MLAs made the process of requesting evidence much more agile in the sense that they are transmitted from one Central Authority to another. Central Authorities are designated within treaties to make this process much more efficient and ensure that countries understand where to channel their requests. MLA Treaties can be bilateral, regional or multilateral. The United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) acts as a multilateral MLA treaty, including for the purpose of asset recovery. The UNCAC has 187 signatories, making it a nearly universal treaty. The UNCAC clearly establishes States Parties obligation to afford one another the widest measure of mutual legal assistance in investigations, prosecutions and judicial proceedings in relation to the offences covered by the Convention, and clearly defines the formal requirements for submitting MLA requests.

Despite efforts to make international legal assistance more agile and less time consuming, it is still one of the greatest hurdles in international asset recovery investigations. In fact, a December 2015 OECD survey found 70% of anti-corruption law enforcement officials report that mutual legal assistance challenges have had a negative impact on their ability to carry out anti-corruption work. Barriers to mutual legal assistance include differences in legal systems and dual criminality, lack of understanding of procedure, and sometimes, even language is an issue. Often, MLA requests are not responded to due to the lack of establishment of a proper causality link between the facts under investigation and the evidence requested. It is important for requesting countries to know that an investigation supporting the request is essential, and above all, an open channel of communication with the requested country will facilitate navigating the waters of what can otherwise be a lengthy and complicated process.

Key considerations for International Cooperation

Practitioners working on asset recovery should keep the following four principles in mind:

A. Incorporate International Cooperation in Each Phase of the Case

Establishing proactive contact early can assist practitioners in understanding the foreign legal system and potential challenges, in obtaining additional leads, and in developing a strategy. It also gives the foreign jurisdiction an opportunity to prepare for its role in providing cooperation.

B. Develop and Maintain Personal Connections

Forming personal connections with foreign counterparts is the hallmark of successful asset recovery cases. A telephone call, an e-mail, a videoconference, or a face-to-face meeting with foreign counterparts will go a long way to moving the case to completion. It is important in all phases: obtaining information and intelligence, making strategic decisions, understanding the foreign jurisdiction’s requirements for assistance, drafting MLA requests, or for following-up on requests for assistance. It helps reduce delays, particularly where differences in terminology and legal traditions lead to misunderstandings. In addition, it can demonstrate that an administration is serious and committed to the case, thereby building trust among the parties and fostering increased attention and commitment to the case.

Despite the difficulty in building personal connections in foreign jurisdictions (due to lack of access to relevant information, resources, language, etc.), the effort is worth the results (integral information to the case, requirements for submitting an MLA request, etc.) and practitioners should make every attempt to build those relationships.

C. Engage in informal assistance channels before, during and after transmitting an MLA request

Many practitioners will immediately resort to drafting an MLA request when they determine that international cooperation is required. However, some important information can be obtained more quickly and with fewer formalities through direct contact with counterpart law enforcement agencies and financial intelligence units, or from liaison magistrates or law enforcement attachés posted locally or regionally. These contacts can also advise on what information is easily accessible in the jurisdiction because it is in the public domain and searchable. Such contacts also offer an opportunity to learn about the procedures and system of the foreign jurisdiction and to assess strategic options. Such informal contacts often need to be cleared through the practitioner’s domestic central authority to ensure that protocol with the other country is not violated and that laws and regulations regarding foreign assistance are observed. It is also a good practice to initiate, develop, and clear these informal contacts with the diplomatic mission in the requested country.

D. Be mindful of potential barriers

Practitioners may encounter many barriers in trying to obtain international cooperation, so it is important that they recognize possible obstacles and take the necessary measures to overcome them. Differences in legal traditions and confiscation systems, jurisdictional issues, procedural variations, legal obstacles, and delays are among the barriers which need to be considered and overcome. Practitioners should be mindful that information provided to a foreign jurisdiction—informally or through a formal MLA request—may result in the foreign jurisdiction initiating its own domestic investigation and subsequently refusing to provide assistance while there are local “ongoing proceedings”. To gauge and navigate these risks, practitioners should use their personal contacts or CARIN or regional networks to learn about the other systems, confirm strategy, and discuss the implications of providing information prior to discussions of substance. To facilitate moving forward without breaching confidentiality or secrecy laws, practitioners will often speak in hypothetical terms during the early phases of the case and planning strategy. For example, “Person x did action y”. How would I achieve the desired outcome in the foreign jurisdiction?”

International Partnerships on Assets Recovery

By helping countries to establish systems to obtain information on the source, destination and ultimate beneficiary of proceeds of crime and corruption, asset recovery networks aim to help asset recovery specialists around the world to fight against corruption and

money laundering.

This directory first examines possible strategies for international cooperation and the distinction between formal mutual legal assistance (MLA) requests and informal assistance. Second, the directory lists the asset recovery networks, along with information about their structure and operations, to help asset recovery specialists access the appropriate networks and cooperate on their crucial efforts to pursue the forfeiture of criminal proceeds.